Not Allowed Out

Dear Nicholas, My memories of the shock of curfew in India are stirred by the current quarantines to stop the spread of coronavirus. I don’t argue with the need for these limits. Still, to be suddenly not allowed out of a small space for an undisclosed period of time is a strange and unforgettable sensation.

Behind Closed Doors

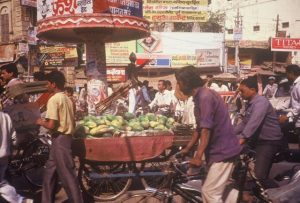

I was in Varanasi, for my long-ago winter in India, on a fellowship to do research for the novel that became my Sister India. I’d been in the city for 17 days when it shut down around me. A city of a million people was told: everyone go to your rooms.

My Varanasi bedroom, with frame for mosquito net

My Varanasi bedroom, with frame for mosquito net

From notes in my journal at the time:

28 October

We expect the possibility of riots soon, another guest said at breakfast.He says this conversationally without visible alarm.This trouble is predictable since it’s almost the anniversary of last year’s trouble over the mosque in Ayodhya, a few rail stops west of here.Hindu fundamentalists threaten to tear down a Muslim mosque there, saying Muslims demolished the 11th century Hindu temple on the site almost five hundred years ago.They don’t intend to let the matter go.

A Time for Riots

9 November

8:30 a.m.

Leah, on the phone, upset. “Banaras korfoo,” said guest flat manager Sakhai. Curfew had begun.

Curfew?

Putting the phone down, Leah told us there had been an incident a little distance from this neighborhood.Hindus were carrying an image of a deity through a Muslim neighborhood to the river; fireworks exploded too close to a house; a fight began; five Hindus, she reported, brutally murdered. What started it was those firecrackers that I’d been hearing since my first day in Delhi.

Hearing the news, Sakhai sank down onto the edge of the sofa, hands on his knees, said in English, “Not good.”

Not Allowed Out

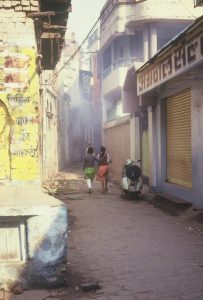

Curfew meant we were not to leave the two bedroom guest flat. Later reports made it uncertain whether it was Hindus or Muslims killed. Donna, another of the Hindi students, stopped by the flat, having ventured out after hearing that the police enforcing curfew would look the other way if you were a foreigner.She had seen the beginning of last night’s incident:the Hindus with the deities seemed aggressive.When she and her friends saw men brandishing sticks, they’d headed into the galis, the narrow lanes, running, afraid that the whole crowded street would pour into the galis and crush them.

The wide entrance to one of the galis

Sitting Around

We spent most of the day sitting around the dining room table talking, the devoutly Hindu Sakhai, at risk (from police, at the very least) if he stepped outside the door.

That night Leah talked by phone to a student who lived at the edge of a Muslim neighborhood: it had been tense there all day, ambulances and trucks of soldiers coming in.I had a sense that “the burning place”–the riverbank cremation pyres–was flaring up in new places here and there across the city, engulfing living people.

10 November

New Delhi paper reports the trouble here, beginning, as Leah said, with the Kali procession and the firecrackers hitting the house of “a person of another community.This,” the account said, “led to some clash in which some elements resorted to heavy brickbatting, arson, stabbing, loot, etc.”No mention of Hindu or Muslim was made in the death counts or anywhere else in the article.

Patches of Freedom

Curfew was still on all day, except for a brief opening in the afternoon for a Krishnalila, a religious dramatic performance on the river. This was the same kind of event as the one that was bombed my first night in India.I decided not to go.Leah and her kids, next-door neighbor Usha’s kids all went, leaving the flat quiet. I felt like a wimp; spent the afternoon working on a rough outline of my novel. When the others returned, I found out I’d missed seeing the maharajah who had attended the ceremony in a boat. I consoled myself with the progress I’d made in developing ideas for the novel.

11November

Leah on the phone: her side of the conversation was like bad theater:”A bomb?” Pause.”Really?” Then she was talking about whether to cross the Durga Kund temple area to get to class. A bomb had gone off, she said, about a kilometer from here, in a home-made lab where people were making explosives.

In our neighborhood, curfew lifted for two hours today, from ten to twelve, staggered openings to allow people to get groceries. Out on break, I saw police jeeps everywhere.When I went to the PO to mail letters, the rolldown metal front was lowered to within two feet of the ground.I crawled under.Inside, a man working by candlelight took my stack of letters to mail.

Reading on the rooftop patio in the afternoon, I heard a spatter of bangs that sounded different than usual. I assumed, though, that it had to be firecrackers, went on with my reading of Banarsi history.

Anger!

Hours later, Leah came back to the flat, saying there had been a gunfight in a nearby neighborhood. So it wasn’t fireworks.It makes me mad, mad at God. (This response now seems to me very young and misdirected.) Anger, though, usually unspoken, is my default response to anything that seems so wrong.

More news from outside the flat:I learned that one person died yesterday at the Krishnalila where Leah and the kids went; police supposedly charged vendors stands with their clubs, because they had opened in violation of curfew. Curfew means that so many people have no income.

Most of what I learn is hearsay or newspapers translated for me; hard to know what is true.We watched the TV national news which is given first in Hindi and again in English.Tonight we made the news. The Hindi version reported that a bomb went off here and killed nine people, the makers of the bomb. The English news didn’t mention it.Maybe they don’t want to scare the tourists.

12 November

Three-hour curfew break for this neighborhood today. Everything comes down to: when will I be able to go out and for how long–when will the killing stop.

This afternoon Usha came to visit, told me I am her American sister, she is my Indian sister.S he has such exuberant warmth, and yet formality as well.The thought comes to me that I might call the novel Sister India.

My intent has been that the story will follow some American travelers to Banaras, who come from the American South; to use as the backdrop of the story the extreme religiosity of both places, the tradition of river baptisms in the South, and the baths in the holy river in Banaras.But now it seems clear that all this violence will somehow come into the story.

Usha also said a five-year-old girl was killed with a knife night before last.Each outbreak of violence seems to bring on a reprisal; this could go on and on.During the break I went to a Hindu temple, saw a man carrying a box under a long scarf, thought:bomb.But it was a box of sweets; I could see the familiar red print, the flimsy paper box.Some nights, I eat the Banarsi sweets, halfway between a candy and a pastry, while I read novels set in India and references on Hindu religion.

13 November

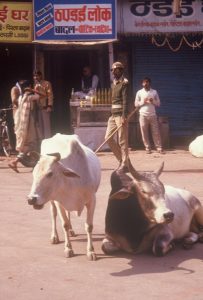

Long break in curfew, 9 to 5! Wonderful! I went out, ran errands, explored and took notes:visited an old tennis club, went to the train station, etc.The city was back to life again.

For the first few minutes, I felt vastly relieved to be out in an open city.And then anger welled up and overwhelmed that.I felt angry–snappish, my neck tense–the rest of the day, as if I’d been saving it up during the days of curfew. I resent Varanasi being reduced to police patrols, curfew, news of killings, rumors.I have the urge to somehow come to the city’s defense, protect the place it is when this is not happening.

I was mad over so many little things, some of the very ones I’ve missed, the press of the crowds and traffic….I want the Varanasi of thosecrowds and the river and the temples, not the Varanasi of violence.Yet riding through the streets, with the city back to normal all around me, I couldn’t get back to normal myself.

Returning to the flat, walking, I came to the edge of a tight gathering in the middle of the street.Trouble. A cop, baring his teeth, was advancing on a rickshaw driver. I asked a man standing near me what was going on. “Fighting,” he said.I hurried away from there, staying close to the wall along the road; police were putting up barricades on the street.

Curfew break was cut short, the city was shutting down. Leah’s son Jimmy came running toward us, said rioting was going on in a nearby Muslim neighborhood and five were dead. We all rushed to the nearby home of one of Leah’s friends; the friend’s mother fed us and tried to explain how political rivalries were the reason for this: for example, a Hindu fundamentalist political group might hire thugs to stir up fighting that can then be blamed on Muslims.Then those fundamentalist politicians can say to the Hindus:elect us and we will protect you from those dangerous people.The Hindi evening news said five had died here today and that Ghurkas, a regiment of the Indian Army, had been sent in.

14 November

Solid curfew, no break. Sakhai told us that 13 Hindu women were killed yesterday, pulled from rickshaws. The numbers are confusing, the death counts different from different sources.The Hindustan Times from New Delhi said eight died here yesterday, four by stabbing, four by a bomb, and in the area where the stabbing incidents occurred, “panic resulted in a stampede.”

It went on for two weeks. Confinement with blips of freedom. I feared that my whole long-awaited winter in India would be consumed by curfew.

But then it was over.

And may it be so with coronavirus! As one Sanskrit mantra says: “May all beings everywhere be happy and free.” Free to go out at will. Free of flashbacks of trouble; mine lasted two years, flashes of imagined violence that I’d never actually seen. Too much time in quiet rooms to think, to visualize.

Peggy

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: able to go out, banarsi history, curfew, curfew in India, current quarantines, Durga Kund, go to your room, Hindu fundamentalists, Kali procession, Krishnalila, mosque in Ayodhya, police enforcing curfew, possibility of riots, riverbank cremation, shock of curfew, shut down, Sister India, sitting around Muslim neighborhood, spread of coronavirus, the burning place, Varanasi, winter in India

Comments

I can certainly see why you were upset; fear, false or misreported news, the unknown and unknowable….I hope I am never put into that position. I remember the emotions stirred in me when I read “Sister India” about those times and the curfew.

It was seriously stirring, kenju. I mostly wasn’t aware of having any fear for myself; I was cautious and not at all a target. But one otherwise silent night after I’d gone to bed, I heard a motorcycle backfire just outside. Adrenaline flooded me.

Very near us is “Durga temple” and very good friend of ours is the female spouse of a priest there, one of many (apparently) if you are up this way sometime. Really loved reading Sister India and all your other books, each exciting in its own way.

I noticed this week a sign went up about two miles from us for a Radha Krishna temple back in the Chatham County woods. A pleasant surprise. Thanks for the kind words about my books.

A very moving entry. I have not yet read Sister India but I think it is next on my reading list. You were very brave.

Thanks, Peggy. My “bravery” was pretty much sitting still and taking notes. Being a foreigner in this instance made me the equivalent of invisible outdoors– an odd sensation in itself. I’m pleased you’re thinking of reading Sister India next. I’d love to know what you think.

I remember this time before I came to visit for 2 weeks – reading again what you told me back then by phone about your experiences is very stirring. You were very brave to be there and go out during the horrors. I’m sure glad you were safe, and so very, very sorry people can be so frightened and cruel to one another.

May we all be safe and healthy, and live peacefully, in contentment, awaken to the light of our true being, and be free.

You are a generous soul, Bob.

[…] do have some experience of quarantine, as I’ve written here before. It was called curfew when I first was part of a lockdown, years ago in India. Riots […]