Beautiful, Mortal: Bodies on the Ganges

(A moment that shook me on my first day in the Hindu holy city of Varanasi, researching my novel Sister India. From “Fire and Holy Water,” an account recently awarded honorable mention in the Soul Making Keats Literary Competition. [Keats wrote that life was not a vale of tears but “a place of soul making.”] )

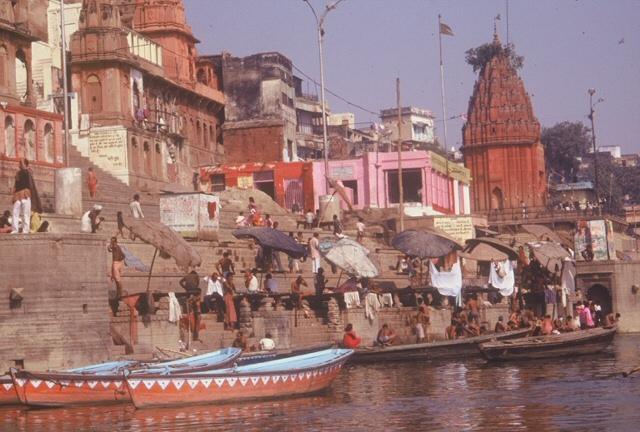

At Dasaswamedh, just beyond the vendors’ tents, I paused to look out before making a descent to the water. Here were people along the water’s edge, bathers, long rowboats, the wide shade umbrellas for the rupee-charging holy men, ready to offer a blessing or keep an eye on a bather’s shoes.

A man stepped up beside me, small and dapper with a cocky air, a straight-backed and lofty bearing. Would I like to have a boat ride? His name was Mamta. His sweetly complacent smile made him seem sure of himself and sure also of his welcome. We started down the long steep steps to the river and the rowboats.

At the edge of the water, we stepped from boat to boat, to reach the one farther out where Mamta’s oarsman was waiting. It was a long wooden open rowboat, just like all the others. We set off down the river, the boatman, shirtless and dark, pulling on long bamboo paddles.

Along the shore here, people were bathing, even though the peak hour had long passed. Men in what looked like hand-wrapped Jockey shorts or thongs. Wiry men with dark muscular butts. The women managing to bathe fully dressed in saris. All along the edge of the water, people were shampooing their hair, soaping their bodies, or scrubbing pots or clothes.

Trash kept floating past the side of the boat–a coconut shell, pieces of charred wood, unrecognizable bits of stuff–the water grey and sudsy. “It looks dirty,” Mamta said, “but push that aside,” sweeping away bits of trash, “and you see it is clean.” He scooped up water in his cupped hand and held it out to show me.

Then we came around the walled edge of a ghat–Manikarnika, the funeral pyres. Three fires burning, three bodies in front of me at the water’s edge. The boatman stopped rowing; we sat and looked. One who dies in Varanasi and gives the ashes to the Ganges becomes part of the eternal and is freed from the cycle of earthly rebirths, that is the Hindu belief. Two more bodies had just been brought here for cremation, each of them wrapped tightly in thin silk, left lying on the bamboo ladder on which the body was carried here.

I could hardly believe I was seeing this. Corpses…lying out in daylight in the sun. They’d been lowered into the Ganges water, Mamta said, and then left on the pavement to dry before burning. The shapes of faces, limbs, knuckles, feet, showed through the silk. They’d wrapped the faces so tight you could see the nose, the hollows of mouth and cheeks and eyes. If someone were still alive, they would suffocate.

Within the high-piled wood of one of the pyres was the bright-colored wrapping of a body, the kindling beneath just beginning to burn.

From the end of the next pyre, I saw what looked like two feet sticking out–could that be? Or was it two pieces of wood I was looking at, bent at the ends? They looked like ankles and feet. I didn’t want to ask Mamta; it seemed prurient to want to know. Whatever they were, I watched as they caught fire and began to burn, turning slowly from “toes-up” to twisted-to-the-side, to downward-turned.

I wanted to scream at that person to wake up, get up from there…fast!

The bodies that lie there aren’t going to wake up, the burning shows you that. …That pair of human feet blistering, searing, to fat, to charred sticks, then ash, as people stared.

The sound of a chant from the top of the ghat–another body was carried into view, up high at city-level, at the top of the stone stairs. The four young men carrying the stretcher calling out a sing-song, “Rama nama…. It had a beat.

A two line chant:

“Ra…ma..na…ma…Sa…tya…hai.”

Again and again. “Rama nama….”

I knew what the words meant: “Rama is the true name, the name of God is truth.” A marching beat. Alluring. On the seat of the rowboat, I felt myself rocking from the waist to that beat.

Down the steps to the water with the body. The four young men lowered it in. It floated. They splashed water on it to make sure it had been completely covered, then pulled it out to dry on the steps with the other wrapped corpses.

A few steps back from the water, a man in only a loincloth, bare-chested, rushed back and forth, through the smoke and haze of burning, tending the flaming pyres, a man of the untouchable old caste of Doms. Yet another pyre flared, ignited with a blazing bundle of twigs waved in circular motion, the flame taken from fire that had been burning at this site for hundreds of years.

I saw no obvious grieving among the groups of men standing at the edge of the ghat. It is said to cause bad fortune for the dead. There were no women in sight. “Women,” Mamta said, “do not want to see their husband or their child burn.”

I stared at those solemn groups of impassive men. Pictured Bob’s long skinny feet. Someone among those men was watching as his beloved burned.

At home, my office in Raleigh is between two funeral parlors, two blocks apart. I see funeral processions every day. Cars. Moving slowly in a line, following the hearse. Nothing to see from my window but sun on the tops of cars.

I felt wrong to be out on the river, intrusive. At the same time I wanted to convince myself that what I was seeing had nothing to do with me, that I shouldn’t be here, seeing the final bows of these bereaved men as, one by one, each approached the corpse, bent low, then moved away.

The night I stood beside my father’s coffin, looked at his body there for the first time, my knees gave way. Standing quietly, my face composed, I felt myself start to drop toward the floor. My brothers, one on either side of me, each caught me by an elbow. We were grown by then, all three of us in our twenties. We had known for a long time that Daddy might have a heart attack. We’d known for so long that I had grown used to the idea of death as something that loomed but never actually happened. He died late at night, at home; he and Mom had just come home from a party. It was fifteen years ago, the night after my return from my earlier trip to India.

I looked around at Mamta; he saw “enough” on my face and signalled the boatman to move us on.

As we set in motion again, I searched the riverbank up ahead for the sight of people doing reassuringly ordinary sights, washing their clothes. I let the faint hot breeze, the growing distance as the oarsman rowed, put the burning pyres behind me and out of my mind.

Then half a mile down the river, beyond the place where we first put in, the boatman accidentally let an oar slip out of his hand into the water. Carried quickly out of his reach, it was coming past me where I sat toward the back of the boat. I reached over the side, grabbed it, passed it back to him, dripping.

The man stared at me, shocked, as if what I had done was astounding, and not a reflex. I gave my hand a wipe on the long blouse of my salwar kameez, childishly pleased with myself that I had unthinkingly reached in. It was now baptized–this hand–in the holy river, dipped halfway to the elbow in grey-green water I had not intended to touch, so murky, full of garbage, laundry soap, bits of charred bone and human ash.

(This nonfiction account was first published in A Woman’s Path: Women’s Best Spiritual Travel Writing. It’s the germ of a scene in my novel Sister India.)

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: bodies, burning, corpses, cremation, death, Ganges, Hindu, holy city, holy men, mortal, pyres, Rama, untouchable, Varanasi

Comments

And an excellent germ it is. I felt while reading, as though I were there. I also felt that many times while reading Sister India. You are so descriptive!

Thanks, kenju. Rereading this (spruced-up) bit from my journal of that time put me back there….

Touching, haunting.

By the time I got back to the Hotel Diamond that afternoon, Linda, I felt touched, haunted, and stunned.

My father’s death was just before, not after, a trip to the far side of Africa (from Virginia), my second trip for one month to Kenya, 1988. I am the first born of eight: my father died just before I turned 44 – in 1988. My baby sister is sixteen years younger than I. At that time she was not quite 28. He (my father), too, died late at night. I did not first see his body in a body / corpse casket but still lying on the hospital bed, IV still connected. When I placed both my open hands on his chest, I could feel well the deep “heat” still radiating from within his body. Brothers and sisters (all younger) had been there. It had taken him less that two days from an emergency 911 call early a Sunday morning to finish dying late the same week’s Monday night (about or after 11:00pm). At that time during my month-long (upcoming) stay for mission work in Kenya, I would not have returned. In those days I might not even have found out until the whole month had passed. I have considered that my father did me a favor to pick that time to die. He turned 72 on May 13, and he died on July 11.

An incredible story, beautifully told. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks, Beth Browne and Bob Braxton. The thought of the “deep heat” is pretty stirring, Bob Braxton.

While he was living, my Father (our family did not hug) when I opened my arms to hug him (in his bib overalls, except when attending church) would turn me aside. Maybe it was Ok for me to hug my mother but not “man to man.” The significance to me was that in death he lay still. My hands could rest on his chest a long, long, long time and he did not pull away or turn to the side away from me. It was important to me to allow that experience to sink in as deeply into my own body / self.

So the moment was even more important than it first seemed, and it was already huge. You describe it well, Bob.

Hi Peggy.

I poignant remembrance to be sure. I remember Varanasi from going there when I was about 20. I also found it a very strong experience to see death so close up. Death is so open in India. In western countries it it much more hidden: the hearse with the darkened windows, the closed casket. Birth is celebrated, and yet in the Bhagavad Gita Krishna says that for one who is born, death is certain. They must go together.

I like how they acknowledge that in India, and I suppose that goes hand in hand with their belief in a next life–that the soul is simply changing bodies.

Such a powerful place! I can’t wait to to again. Thanks for your evocative writing.

I don’t think anyone ever forgets Varanasi, BTLowry. I feel like I lived a separate extra life there in 3 months. And I love that you have Ursula LeGuin speaking on your website.